To use this site, please enable javascript

To use this site, please enable javascript

Just over a hundred years ago, the only major naval battle of WWI – the Battle of Jutland – took place off the west coast of Denmark. More than twenty ships were lost, both British and German, and both sides claimed victory – but precisely how the battle unfolded has remained a mystery, due to conflicting accounts, the odd scandal, and the fact that the wrecks lay too far down in too cold of water to be effectively surveyed by divers.

In the last decade, though, multi-beam echo sounder (MBE) survey technology for remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) has made tremendous progress. Now, survey software such as EIVA NaviSuite can provide high-quality mappings of wreck sites, offering many more possibilities than divers’ reports.

Recently, this technology was taken advantage of by researchers. In 2015, nautical archaeologist and historian Dr Innes McCartney of Bournemouth University joined a dedicated marine survey of the Jutland battlefield, using EIVA NaviSuite software to survey and model the wrecks.

'Since I began to work with JD-Contractor and the Sea War Museum Jutland, I have been using NaviSuite and in particular NaviModel Producer in conjunction with our multibeam surveys of shipwrecks. I find NaviModel an excellent tool for producing high quality images for my work and publications. I am impressed with the simple interface which makes working with point clouds and digital terrain models very straightforward. I am delighted to be an academic partner with EIVA,' said Dr Innes McCartney.

With the marine survey, Dr McCartney hoped to shed light on how the battle had progressed, and what exactly had happened to each lost ship. He has now published his research in a book, titled 'Jutland 1916: The Archaeology of a Naval Battlefield'. In this book, he reconciles what was believed to have occurred back then to what the archaeology now shows – giving a clearer picture than ever before of what happened on that spring night in 1916.

Here, we present the book’s introduction to give you a glimpse of this groundbreaking research that EIVA was privileged to be a part of.

'Jutland 1916: The Archaeology of a Naval Battlefield' is available on Amazon.com and all other domains. You can also follow Dr McCartney’s work, as well as the research of the Bournemouth University Maritime Archaeology department.

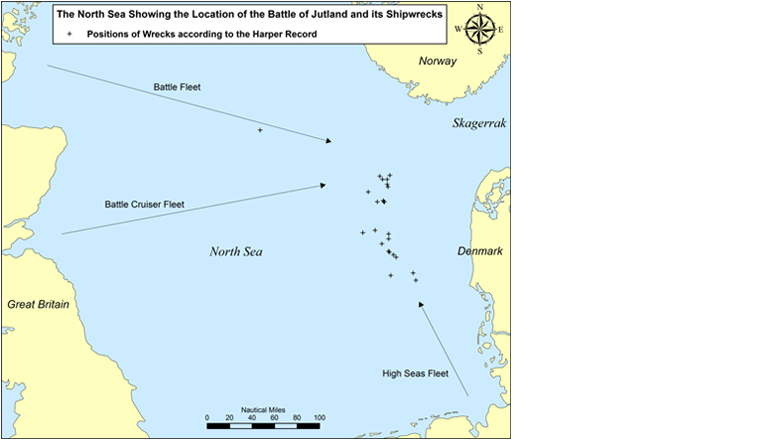

On 31 May to 1 June 1916 the two largest battle fleets in the world clashed in the North Sea, off the coast of Denmark (Fig. i). The positions of the wrecks are derived from the record of the battle compiled by the Royal Navy's director of navigation, Captain JET Harper in 1919, sometimes referred to as the Harper Record.

Fig. i Map showing the location of the Battle of Jutland and the routes taken by the British and German fleets. The black crosses mark the historical positions of the shipwrecks as recorded in the Harper Record. The battlefield covers more than 3,000 nautical square miles.

The Battle of Jutland was more of a skirmish than a set-piece naval battle. In effect, the German High Seas Fleet ‘blundered into the stronger British Grand Fleet while chasing what it assumed to be an isolated part of that fleet.’ Facing impossible odds, the High Seas Fleet skilfully turned around and slipped away into the mists of the North Sea, leaving the Royal Navy in command of the battlefield. Germany never risked a fleet encounter again and increasingly turned to the U-boat as a means of pursuing the naval war.

Although a seemingly strategic victory for the Royal Navy, Jutland was no Trafalgar. The German fleet avoided defeat and the price paid by the isolated part of the British fleet, Admiral Beatty’s Battlecruiser Fleet, was tragically high. Of the 249 ships that fought in the Battle of Jutland, 25 were sunk, claiming 8,500 lives in the process. The Royal Navy’s share of these losses was 14 of the ships and 6,000 of the dead.

More than 5,000 of the British casualties occurred in the five largest warships lost, the battlecruisers HMS Indefatigable, Queen Mary and Invincible, and the armoured cruisers HMS Defence and Black Prince. These ships suffered fatal internal explosions from which very few survived. The disappointment felt in Britain became the source of much acrimony in the years following the battle. More has been published about the Battle of Jutland than any other naval encounter. But aside from my academic papers, this book is the first detailed study of the shipwrecks.

The total number of wrecks in the main battlefield area, and under investigation here, is 24. This omits the HMS Warrior, which sank on her return voyage owing to damage sustained in the battle (see Fig. i, where it is the one wreck plotted between Norway and Scotland, out of the main battlefield).

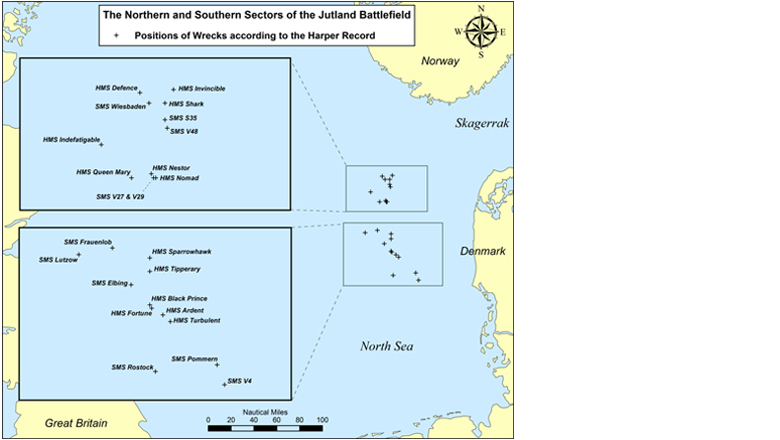

The Battle of Jutland covers an area of around 3,772 nautical square miles. It was fought over 16 hours and in reality was a collection of three different and quite distinct actions; the Battlecruiser Action, the Fleet Action and the Night Action, which fall into two distinct groups of wrecks (Fig. ii).

Fig. ii Map showing the two distinct groupings of wrecks that characterise the Jutland battlefield. The northern sector contains the wrecks of the daylight actions.

Initially the Battlecruiser Action broke out when the Battlecruiser Fleet engaged the German First Scouting Group made up of Admiral Hipper's battlecruisers on what became known as the ‘Run to the South’ during which time both HMS Indefatigable and Queen Mary were sunk.

With the arrival from the south-east of the main German battle fleet, the Battlecruiser Fleet turned around and headed towards Jellicoe who was approaching from the north-west. By this time the Battlecruiser Fleet was being protected by the fast battleships of the Fifth Battle Squadron which had been attached to it but had been left behind at the start of action. This phase of the Battlecruiser Action has become known as the ‘Run to the North’. At the apex, where the turn north was made, the opposing light forces clashed; two destroyers (British light vessels) and two torpedo boats (German light vessels) were sunk.

The Fleet Action is characterised as the period when the British battle fleet deployed into its fighting line, catching the German battle fleet off guard and forcing it to turn away completely on two occasions before it was able to disentangle itself from the British and escape into the enclosing dusk. The British lost the battlecruiser Invincible, the armoured cruiser Defence and one destroyer, while the Germans lost the light cruiser Wiesbaden and two torpedo boats. The distinct nature of the wreck distribution in the Battlecruiser and Fleet two actions is shown in Fig. iii.

Fig. iii Map showing the northern group of wrecks segmented into the lower Battlecruiser Action and the upper Fleet Action.

The rest of the battle is characterised by the scuttling of German ships and by a number of clashes between opposing ships at night, usually at extremely short range. During these actions the German fleet managed to pass behind the British fleet as it attempted to screen the coast of Denmark and keep the German fleet at sea for battle the following day. The German fleet made good its escape and in the morning the British returned to base.

During the Night Action, Germany lost the battleship SMS Pommern, the battlecruiser Lützow, the light cruisers Elbing, Rostock and Frauenlob and one torpedo boat, V4. The British lost the armoured cruiser Black Prince and five destroyers, Tipperary, Sparrowhawk, Ardent, Fortune and Turbulent.

The ships lost remained unseen to all but a few until 1991 when at the time of the 75th anniversary of the battle, the first of the wrecks (HMS Queen Mary, Invincible and SMS Lützow) were filmed for television. Since then, more of the wrecks have been discovered and modern shipwreck archaeology has emerged as a distinctive field of study.

The nautical archaeology of modern shipwrecks as a discipline can trace its formative roots back as least as far as the Cold War. Early cases tended to focus on the need to explain why certain military assets had sunk and were largely secret, but their investigative approaches share much with the modern discipline. Everything changed in 1985 with the discovery of RMS Titanic which popularised iconic modern shipwrecks. Many other finds followed, not least the first of the Jutland shipwrecks.

In the popular imagination at least, wrecks of this type could confirm and demonstrate exactly what contemporary reports of their sinking stated. In other words, the wrecks initially tended to function as friendly witnesses and, although interesting, were largely incidental to the central historical tale of wreck and loss. (In many ways this fits with a broader perception that historical archaeology is little more than the handmaiden of history.) This, however, seriously underestimates the archaeological potential of the wrecks themselves.

Modern shipwrecks can significantly contribute to our understanding of historical events if the bodies of the wrecks are subject to a kind of scrutiny that seeks to go beyond the original historical depiction of the sinking, adopting an approach closer to that used by the investigators of lost Cold War naval assets. I have attempted to do this with the wrecks of the Battle of Jutland and in the study of more than 100 U-boat wrecks and am not alone in using this approach.

While all shipwrecks can offer some element of new information as to how they sank, the scale of the new data obviously varies from case to case. Some wrecks, such as HMS Queen Mary, have proven to be revelatory in what they can offer. Others, such as SMS Lützow, have told us little aside from the fact that portions of the ship have been salvaged. Yet every wreck has at least revealed something new that has added to our understanding of Jutland.

Importantly, it has become increasingly clear that there is plenty left to learn about the technologies used on the sunken ships. For example, in her time HMS Queen Mary was among the most complex structures ever built. No single person would have understood even a small portion of the myriad technologies she contained. Today few know much about how she really functioned and this is one of the major challenges faced by archaeologists when examining complex modern shipwrecks; something my colleagues who prefer the certainties of ancient dug-out canoes have never had to think about.

Battlefield archaeology is not normally associated with nautical contexts. Owing to the unique circumstances of naval conflict, the challenges faced by the nautical archaeologist are different from land contexts. I have previously published a detailed study of the U-boat wrecks in the English Channel from both world wars and have placed the findings in the contexts of the battlefields in which they were lost.

In that case, my approach was to view the wrecks both individually and collectively and compare the results of the 63 wreck surveys with the original Allied documents which, up until then, had been the dominant force in informing the historical record. The results revealed a wide variance in the accuracy of the Allied naval intelligence records and demonstrated the value of examining shipwrecks on the battlefield level.

At Jutland, I’ve adopted a not entirely dissimilar approach. The distribution of the wrecks has been benchmarked against the best geographically referenced charts of the battle to find differences and similarities. Where the two datasets coincide and conflict with each other they can potentially tell us much about how the records were compiled and how the battle was viewed by its participants.

Original copies of the Harper Record are difficult to find. Until recently I only ever worked from two now quite ragged photocopies. But from the first time I saw it I knew that the Harper Record was a very useful source document to anyone who sought to explore the battlefield. This is because it seemingly is agenda-free and simply a chronology of the battle, giving the positions of where Harper thought the ships sank – most useful to an archaeologist. The Harper charts are even rarer than the Record; I hope readers will appreciate just how useful they are.

It is difficult not to admire the work carried out by Captain JET Harper, his team of four officers and their assistants in compiling what is commonly referred to as the Harper Record. It was the first and, as it turned out, the only attempt made by the Admiralty to produce an honest, unvarnished version of events. Other Admiralty portrayals of the battle are sadly contaminated with varying degrees of agenda-laden falsehoods. The reason that it failed to see publication in its original impartial version, with charts, had nothing to do with the quality of Harper’s work.

Fig. iv In 1919 (left), head of the Royal Navy Navigational School, was tasked with producing a chronological and geographical record of the Battle of Jutland. The subsequent blocking of its publication became the source of much controversy in the inter-war years. In 1927, when retired, Rear-Admiral Harper published his own version of events, The Truth About Jutland, as referenced in the newspaper article to the right. This stoked further controversy and forced the Admiralty to finally release an edited version of the Harper Record, without its charts (Pictures: National Portrait Gallery, left; London Evening Standard, right)

The compilation of the Harper Record must have been a colossal undertaking. According to Harper: ‘My orders were to prepare a Record, with plans, showing in chronological order what actually occurred in the battle. No comment or criticism was to be included and no oral evidence was to be accepted. All statements made in the Record were to be in accordance with evidence obtainable from Admiralty records’. From February to September 1919 Harper and his team worked through the mass of charts, tracings, gunnery records and other reports. Permission was sought in April to locate the wreck of HMS Invincible and it was duly found in July, allowing Beatty's and Jellicoe's tracks to be reconciled.

The Harper Record was submitted in October 1919 but not seen in public in anything like its original form until 1927 and even then without its charts. The charts were never officially published. Instead, in 1920 the Admiralty published Jutland Dispatches, a compilation of original reports, charts and signals from the battle. Although remarkably detailed, it was unintelligible to the average reader. Some alterations to original documents had also been made, not least to HMS Lion's movements.

By the time the Harper Record was published in 1927 (seemingly to conflict with the launch of Harper's The Truth About Jutland, published at the same time), Harper had disassociated himself from a number of corrections that he felt had been forced upon him, not least on some of the charts which, he felt, erroneously portrayed the movements of the Battlecruiser Fleet after 17.00 on 31 May 1916. Harper never hid his bitterness about how the Record had been subverted.

The unsightly ‘Jutland Scandal’ into which the Harper Record was drawn is outside the scope of this book, but it was seemingly too soon after the battle to attempt an impartial record of events. The author Leslie Gardiner put it succinctly: ‘Too many Jutland veterans were still alive, still engaged in a longer running fight, the promotion battle, still anxious to clear their individual yardarms after the action’. As a consequence, Harper's task was something of a poisoned chalice. It mattered little just how impartial or accurate the Harper Record actually was because in any case it would inevitably find its detractors. They came in the form of Admiral Beatty who, having just been made First Sea Lord, found the Harper Record awaiting his approval when he arrived at the Admiralty. It was Beatty who blocked its progress through official and unofficial means.

By comparison with Harper, geographic data is missing from many other histories, even though they were published replete with maps. Notably Corbett, Groos and Marder did not geographically reference their diagrams and only some of the charts in Jutland Dispatches are geographically referenced. Therefore in the study of the Battle of Jutland at the battlefield level the Harper Record is a very important source document. Its geographical referencing means that the charts can be digitised and accurately incorporated into the electronic charting of the battle. This is how the maps presented in this study were compiled.

There are a number of other sources that have continually proved of use while researching the wrecks. The National Archives hold a great deal of material on the battle; the reports of commanders and maps and records of the German Navy compiled by the Intelligence Division have all proved invaluable. All sources used have been referenced throughout the text. Of particular use has been the Admiralty translation of the official German history of the Battle of Jutland. The original ship's plans of many of the wrecks sunk at Jutland are housed at the National Maritime Museum and have proven invaluable in deciphering much of the archaeology recorded.

Aside from the archival sources, innumerable published sources have been consulted throughout the years. The most useful include Campbell's Analysis of the Fighting, Friedman's compilation of British intelligence sources on the German Navy, March's superb history of British destroyers, Parkes's companion volume on British battleships and Gordon's Rules of the Game.

The most useful eyewitness accounts in researching the shipwrecks tend to be those from survivors of ships that sank or those who witnessed the destruction of others, preferably recorded as soon after events as possible. Eyewitness accounts can be revelatory but also very inconsistent and unreliable. For example, one survivor from HMS Queen Mary recalled in 1972 that the ship was torpedoed and took 20 minutes to sink when in reality she took little more than a few seconds to sink after shellfire caused a magazine detonation.

You can also imagine a situation where the ships’ crews all talked to each other about the battle in the hours afterwards, affecting each participant's memory of events. By the time the Grand Fleet arrived back in Britain each ship could have, to a greater or lesser degree, developed her own personal account of events. It is important to recognise this and take a somewhat less than sanguine view of what eyewitnesses have to offer.

Inevitably some accounts tend to ring truer than others. Perhaps this is just personal preference, but as much as possible the selection of eyewitness accounts used in this book has been drawn from those which tend to support what the archaeology of the wrecks is telling us; however, this is not always the case. In instances where practically nothing is known of what happened to a ship, whatever eyewitness accounts are available have been used as evidence for consideration.

By far the most valuable published volumes of eyewitness accounts are those by Fawcett & Hooper and Steel & Hart. Accounts from both sides can be found in the National Archives, Leeds University Library and the Imperial War Museum. The researchers Peter Liddle and Robert Church in particular are owed a great debt of gratitude for recording the words of so many of Jutland's participants during the 1970s and 80s.

The purpose of this book is to place a full written record of the fieldwork in which I have been involved on the Jutland shipwrecks in the public domain in time for the 100th anniversary of the battle. Although we now know the exact locations and identities of 22 of the wrecks, this study is not definitive, but it has reached a point where the results have become extensive enough to form a springboard for future research.

The motivation behind my earliest dives on the Jutland wrecks was the sort of curiosity which all explorers seem to share. But as time passed and my understanding of what was there began to grow, it became apparent that the wrecks had a unique story to tell. By examining their remains it was possible to contribute significantly to the history of the battle. The next step was to try to define in archaeological terms what this actually meant. Studying archaeology to PhD level certainly helped me in this as did my surveys of countless submarine wrecks.

Diving or surveying wrecks and seeing how what is there is confirmed by the history books may make nice television, but it is not archaeology. To do that is fulfil the ‘the fallacy of affirming the consequent’ and once you know what it is, you see it all the time. The acid test is to ask yourself: ‘if we know this anyway, why are we here?’ It’s better to ask how the shipwrecks can shed light on what we do not know, but could find out if we looked?

In the case of the Battle of Jutland, in particular, a major constraint on the archaeologist is the sheer weight of archival and written information about the battle. The archaeologist needs to have a working knowledge of this literature; of a highly complex battle involving highly complex ships, battle fleets’ fighting instructions and so on.

Moreover, in common with many modern shipping losses, there is a plethora of eyewitness accounts and descriptions of events which depict, sometimes in great detail, the building, life, roles, purposes and losses of the ships under investigation. This has led some to doubt whether such shipwrecks have any archaeological worth. This debate reached a crescendo over the wreck of the RMS Titanic, when it was claimed the site had no archaeological merit.

The case of the USS Arizona shares similarities with the Jutland wrecks. There, symbolically laden terms such as ‘war-grave’ and ‘desecration’ meant that the archaeologists have undertaken not to enter the wreck and be conscious of considerations as to how their findings may be displayed. Similarly, the TV producers gave undertakings to the Ministry of Defence (MOD) not to disturb or enter the Jutland wrecks, nor to depict images of a perceived emotive nature when we were making the television documentary Clash of the Dreadnoughts in 2003.

Within the constraints described above, there are two major categories that shaped the fieldwork carried out on the wrecks:

Firstly, the wreck sites offer an opportunity to assess the reports of how the ships were destroyed and the myriad of eyewitness accounts and weed out incorrect interpretations of events. At the same time, they can also contribute new and unique data to what was previously known about how the ships sank. As you’ll find out, the extant remains of many of the Jutland wrecks have significantly enhanced the history of the battle, especially in those cases where either the chaos of events or the lack of survivors has led to a great deal of speculation in the past.

Secondly, the accurate wreck positions offer the opportunity to produce a better map of where the losses actually occurred, which could potentially lead to a greater understanding of the battle and help assess the accuracy of various conflicting accounts of what happened. In geographical terms at least, they offer the possibility to measure the accuracy of official track charts and reports. Ultimately the most detailed studies, such as the Harper Record, can be re-examined to see how and why elements were either correctly or incorrectly portrayed.

Beyond these two objectives, the surveys were also essential to identify the smaller wrecks and, in so doing, highlighting what remains of them and how they are rapidly deteriorating. Furthermore, they also uncovered an unsavoury record of illegal salvage for profit on several sites.

Before the battlefield could be accurately mapped, the wrecks needed to be identified. There were no real issues with the larger ones, because of their comparative uniqueness. However, the destroyers and torpedo boats did need to be specifically identified and this required fieldwork and detailed archaeological analysis.

Along with the examination of the wrecks for archaeological purposes, we assessed just how much remains of them and attempted to gauge how much longer they will remain in a condition in which they remain worthy of study. During this type of assessment we realised that increasing numbers of the wrecks have been subject to salvage for profit in recent years, causing damage to the sites and seriously disrupting their archaeological potential.

Early on we recognised that the North Sea presents some tricky challenges to those who wish to survey the Jutland wrecks. The cold and the depth of the wrecks are major limiting factors to what divers can hope to achieve in the short duration they have on each dive. On the deeper wrecks, helium-enriched gasses are essential, bottom time is short and decompression is long. The limited time and the sheer size of the Jutland wrecks mean that traditional methods of wreck recording by divers are hopelessly impractical. The best way to record what is seen is to use a video camera on every dive, and over time bring together an overall picture of what is present.

Better still is to employ a ROV, which does not labour under the time constraints imposed on divers. The ROV work in 2003 really opened up the potential for detailed study and was the basis behind my papers on HMS Defence and HMS Invincible. The ROV worked better than diving because of the time that could be spent examining the wrecks, but it was not perfect. The ROV employed on these surveys had the potential to see much but disorientation was always a possibility as there was no telemetry recorded. What was really required to build up accurate site maps was geophysics.

In 2003 some side scan passes were made, showing the potential of this technology on a dedicated expedition. Multibeam imaging was still not producing the type of resolution required to make it useful on the deeper wrecks. However, by 2008 this had changed. I was involved in the making of a documentary about the loss of the Dreadnought HMS Audacious to a mine in 1914. During the filming, multibeam imaging was employed (see Fig. v) and the results were very helpful in mapping the wreck site, understanding how she had sunk and revealing how she had subsequently collapsed as a shipwreck.

Fig. v Multibeam image of the wreck of HMS Audacious, taken in 2008. It shows the wreck to be upside down, with the bows broken away and folded back towards the stern. The extent to which the wreck has collapsed is revealed by its internal features being visible.

Clearly this technology would be essential to figure out what is present on the Jutland battlefield. So it was with great enthusiasm that I accepted the chance to work as Gert Normann Andersen's number two on a dedicated multibeam survey of the Jutland battlefield in 2015. The EIVA multibeam system in use on MV Vina is state of the art and has really helped push the study of the Jutland battlefield to another dimension. This expedition also happily coincided with the discovery of so many of the smaller shipwrecks, which, with one exception, had eluded us during the diving expeditions. The challenge that remained was to identify these smaller wrecks.

The multibeam results of the April 2015 survey revealed a number of wrecks which were likely to be torpedo boats and destroyers. Some had been confirmed as such by the ROV. In many cases the wrecks were very corroded; in some cases right down to the boilers being the only remaining recognisable features. So a methodology needed to try to differentiate the sites.

I decided to develop a typology which could, if the wrecks yielded enough clues, be used to distinguish each wreck down to the class of ship to which she was built. This involved inspecting the original builder's plans of all the classes of destroyers and torpedo boats sunk at Jutland. The 13 smaller ships sunk fell into six classes. The lower deck and hold plans of these classes showed clearly how the heavy machinery within each class was distributed within their hull forms. Each class of warship turned out to be sufficiently different to allow a very useful tool to be developed (Fig. vi).

Fig. vi Typology of the six classes of destroyers and torpedo boats lost at Jutland. The typology is based on the overall dimensions of their hull forms and the distribution of the boilers, turbines and condensers. These tend to be most common surviving features easily detectable on multibeam, for which this typology was developed alongside.

The typology was based on the supposition that what appeared on the multibeam images was likely to be the types of heavy machinery that have survived 100 years underwater, notably the boilers, condensers and turbines. The distribution of these features is significantly different from class to class. For example, HMS Tipperary has a unique number of boilers, whereas the German vessels tended to have more compact double engine rooms, thanks to the use of the Föttinger transformer system. British designs tended to have a single engine room and employed both cruising and high-pressure turbines. As it turned out, this typology proved to be useful in differentiating the smaller wrecks down to the class level. One common piece of machinery across nearly all of the warships sunk at Jutland was the three-drum boiler. This was a boiler system that used three drums in a triangular configuration, with the heat source in the middle heating the upper drum, known as the steam drum. There were three different designs in use among the smaller vessels (Fig. vii). We hoped that from the ROV data it would be possible to distinguish the types of boiler on each ship based on these design differences.

Fig. vii shows the subtle differences: The boilers are displayed in a split diagram which shows the internals on one side and what they looked like completed on the other. The boiler in common use in the Royal Navy was the Yarrow type (A), characterised by its absolutely straight water tubes and the oval nature of the bottom two tubes, known as water troughs. The White-Forster type seen exclusively on the wreck of HMS Tipperary (B) looked very similar to the Yarrow type, but the tubes are gently curved. The German navy seems to have almost exclusively used the Schulz-Thornycroft boiler, often called simply the ‘marine type’. The version in Fig. vii (C) has four tubes, but this system came in two- to four-tube variants. The Schulz-Thornycroft type is characterised by very obviously curved water tubes and circular water troughs. All three types of boiler are visible on the Jutland wrecks.

Fig. vii The three types of three-drum boiler in use in the smaller warships sunk during the Battle of Jutland. Yarrow (A) is the common British type, White-Forster was used in HMS Tipperary (B), and the Schulz-Thornycroft type (C) was in extensive use in the Imperial German Navy. (Picture: Stoker's Manual, 1911)

As much as possible, the timings used have been derived from the Harper Record. These are British (GMT) time, which is an hour behind the times used by the German High Seas Fleet (CET) and generally seen in German accounts of the battle.

Imperial measurements have been used to describe the ships and events in a historic context, while metric measurements have been to discuss the archaeology of the wrecks and modern interpretations of the results. This was the simplest convention to use as events happened when Britain used the imperial system and the archaeology developed as a discipline after the metric system came into use.